Before November 1976, a firm could arrange to use an asset through a lease and not disclose the asset or the lease contract on the balance sheet. Lessees needed only to report information on leasing activity in the footnotes of their financial statements. Thus, leasing led to off–balance-sheet financing.

In November 1976, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued its

Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 13 (FAS 13), “Accounting for Leases.”

Under FAS 13, certain leases are classified as capital leases. For a capital lease, the present value of the lease payments appears on the right-hand side of the balance sheet. The identical value appears on the left-hand side of the balance sheet as an asset.

FASB classifies all other leases as operating leases, though FASB’s definition differs from that of nonaccountants. No mention of the lease appears on the balance sheet for operating leases.

The accounting implications of this distinction are illustrated in Table 21.1. Imagine a firm that, years ago, issued $100,000 of equity in order to purchase land. It now wants to use a $100,000 truck, which it can either purchase or lease. The balance sheet reflecting purchase of the truck is shown at the top of the table. (We assume that the truck is financed entirely with debt.) Alternatively, imagine that the firm leases the truck. If the lease is judged to be an operating one, the middle balance sheet is created. Here, neither the lease liability nor the truck appears on the balance sheet. The bottom balance sheet reflects a cap-

ital lease. The truck is shown as an asset and the lease is shown as a liability.

Accountants generally argue that a firm’s financial strength is inversely related to the amount of its liabilities. Since the lease liability is hidden with an operating lease, the balance sheet of a firm with an operating lease looks stronger than the balance sheet of a firm with an otherwise-identical capital lease. Given the choice, firms would probably classify all their leases as operating ones. Because of this tendency, FAS 13 states that a lease must

be classified as a capital one if at least one of the following four criteria is met:

1. The present value of the lease payments is at least 90 percent of the fair market value of the asset at the start of the lease.

2. The lease transfers ownership of the property to the lessee by the end of the term of the lease.

3. The lease term is 75 percent or more of the estimated economic life of the asset.

4. The lessee can purchase the asset at a price below fair market value when the lease expires. This is frequently called a bargain-purchase-price option.

These rules capitalize those leases that are similar to purchases. For example, the first two rules capitalize leases where the asset is likely to be purchased at the end of the lease period. The last two rules capitalize long-term leases.

Some firms have tried to cook the books by exploiting this classification scheme.

Suppose a trucking firm wants to lease a $200,000 truck that it expects to use for 15 years.

A clever financial manager could try to negotiate a lease contract for 10 years with lease payments having a present value of $178,000. These terms would get around criteria (1) and (3). If criteria (2) and (4) could be circumvented, the arrangement would be an operating lease and would not show up on the balance sheet.

Does this sort of gimmickry pay? The semistrong form of the efficient-capital-markets hypothesis implies that stock prices reflect all publicly available information. As we discussed earlier in this text, the empirical evidence generally supports this form of the hypothesis. Though operating leases do not appear in the firm’s balance sheet, information on these leases must be disclosed elsewhere in the annual report. Because of this, attempts to keep leases off the balance sheet will not affect stock price in an efficient capital market.

TAXES,THE IRS, AND LEASES

The lessee can deduct lease payments for income tax purposes if the lease is qualified by the Internal Revenue Service. Because tax shields are critical to the economic viability of any lease, all interested parties generally obtain an opinion from the IRS before agreeing to a major lease transaction. The opinion of the IRS will reflect the following guidelines:

1. The term of the lease must be less than 30 years. If the term is greater than 30 years, the transaction will be regarded as a conditional sale.

2. The lease should not have an option to acquire the asset at a price below its fair market value. This type of bargain option would give the lessee the asset’s residual scrap value, implying an equity interest.

3. The lease should not have a schedule of payments that is very high at the start of the lease term and thereafter very low. Early balloon payments would be evidence that the lease was being used to avoid taxes and not for a legitimate business purpose.

4. The lease payments must provide the lessor with a fair market rate of return. The profit potential of the lease to the lessor should be apart from the deal’s tax benefits.

5. The lease should not limit the lessee’s right to issue debt or pay dividends while the lease is operative.

6. Renewal options must be reasonable and reflect fair market value of the asset. This requirement can be met by granting the lessee the first option to meet a competing outside offer.

The reason the IRS is concerned about lease contracts is that many times they appear to be set up solely to avoid taxes. To see how this could happen, suppose that a firm plans to purchase a $1 million bus that has a five-year class life. Depreciation expense would be $200,000 per year, assuming straight-line depreciation. Now suppose that the firm can lease the bus for $500,000 per year for two years and buy the bus for $1 at the end of the two-year term. The present value of the tax benefits from acquiring the bus would clearly be less

than if the bus were leased. The speedup of lease payments would greatly benefit the firm and de facto give it a form of accelerated depreciation. If the tax rates of the lessor and lessee are different, leasing can be a form of tax avoidance.

THECASH FLOWS OF LEASING

In this section we identify the basic cash flows used in evaluating a lease. Consider the decision confronting the Xomox corporation, which manufactures pipe. Business has been expanding, and Xomox currently has a five-year backlog of pipe orders for the Trans-Honduran Pipeline.

The International Boring Machine Corporation (IBMC) makes a pipe-boring machine that can be purchased for $10,000. Xomox has determined that it needs a new machine, and the IBMC model will save Xomox $6,000 per year in reduced electricity bills for the next five years. These savings are known with certainty because Xomox has a long-term electricity purchase agreement with State Electric Utilities, Inc.

Xomox has a corporate tax rate of 34 percent. We assume that five-year straight-line depreciation is used for the pipe-boring machine, and the machine will be worthless after five years.

However, Friendly Leasing Corporation has offered to lease the same pipe-boring machine to Xomox for $2,500 per year for five years. With the lease, Xomox would remain responsible for maintenance, insurance, and operating expenses.

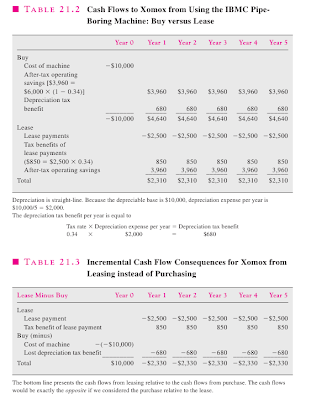

Simon Smart, a recently hired MBA, has been asked to calculate the incremental cash flows from leasing the IBMC machine in lieu of buying it. He has prepared Table 21.2, which shows the direct cash flow consequences of buying the pipe-boring machine and also signing the lease agreement with Friendly Leasing.

To simplify matters, Simon Smart has prepared Table 21.3, which subtracts the direct cash flows of buying the pipe-boring machine from those of leasing it. Noting that only the net advantage of leasing is relevant to Xomox, he concludes the following from his analysis:

1. Operating costs are not directly affected by leasing. Xomox will save $3,960 (after taxes) from use of the IBMC boring machine regardless of whether the machine is owned or leased. Thus, this cash flow stream does not appear in Table 21.3.

2. If the machine is leased, Xomox will save the $10,000 it would have used to purchase the machine. This saving shows up as an initial cash inflow of $10,000 in year 0.

3. If Xomox leases the pipe-boring machine, it will no longer own this machine and must give up the depreciation tax benefits. These tax benefits show up as an outflow.

4. If Xomox chooses to lease the machine, it must pay $2,500 per year for five years. The first payment is due at the end of the first year. (This is a break, because sometimes the first payment is due immediately.) The lease payments are tax-deductible and, as a consequence, generate tax benefits of $850 (0.34 ϫ $2,500).

Of course, the cash flows here are the opposite of those in the bottom line of Table 21.3.

Depending on our purpose, we may look at either the purchase relative to the lease or vice versa. Thus, the student should become comfortable with either viewpoint. Now that we have the cash flows, we can make our decision by discounting the flows properly. However, because the discount rate is tricky, we take a detour in the next section before moving back to the Xomox case. In this next section, we show that cash flows in the lease-versus-buy decision should be discounted at the after-tax interest rate (i.e., the after-tax cost of debt capital).

In November 1976, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued its

Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 13 (FAS 13), “Accounting for Leases.”

Under FAS 13, certain leases are classified as capital leases. For a capital lease, the present value of the lease payments appears on the right-hand side of the balance sheet. The identical value appears on the left-hand side of the balance sheet as an asset.

FASB classifies all other leases as operating leases, though FASB’s definition differs from that of nonaccountants. No mention of the lease appears on the balance sheet for operating leases.

The accounting implications of this distinction are illustrated in Table 21.1. Imagine a firm that, years ago, issued $100,000 of equity in order to purchase land. It now wants to use a $100,000 truck, which it can either purchase or lease. The balance sheet reflecting purchase of the truck is shown at the top of the table. (We assume that the truck is financed entirely with debt.) Alternatively, imagine that the firm leases the truck. If the lease is judged to be an operating one, the middle balance sheet is created. Here, neither the lease liability nor the truck appears on the balance sheet. The bottom balance sheet reflects a cap-

ital lease. The truck is shown as an asset and the lease is shown as a liability.

Accountants generally argue that a firm’s financial strength is inversely related to the amount of its liabilities. Since the lease liability is hidden with an operating lease, the balance sheet of a firm with an operating lease looks stronger than the balance sheet of a firm with an otherwise-identical capital lease. Given the choice, firms would probably classify all their leases as operating ones. Because of this tendency, FAS 13 states that a lease must

be classified as a capital one if at least one of the following four criteria is met:

1. The present value of the lease payments is at least 90 percent of the fair market value of the asset at the start of the lease.

2. The lease transfers ownership of the property to the lessee by the end of the term of the lease.

3. The lease term is 75 percent or more of the estimated economic life of the asset.

4. The lessee can purchase the asset at a price below fair market value when the lease expires. This is frequently called a bargain-purchase-price option.

These rules capitalize those leases that are similar to purchases. For example, the first two rules capitalize leases where the asset is likely to be purchased at the end of the lease period. The last two rules capitalize long-term leases.

Some firms have tried to cook the books by exploiting this classification scheme.

Suppose a trucking firm wants to lease a $200,000 truck that it expects to use for 15 years.

A clever financial manager could try to negotiate a lease contract for 10 years with lease payments having a present value of $178,000. These terms would get around criteria (1) and (3). If criteria (2) and (4) could be circumvented, the arrangement would be an operating lease and would not show up on the balance sheet.

Does this sort of gimmickry pay? The semistrong form of the efficient-capital-markets hypothesis implies that stock prices reflect all publicly available information. As we discussed earlier in this text, the empirical evidence generally supports this form of the hypothesis. Though operating leases do not appear in the firm’s balance sheet, information on these leases must be disclosed elsewhere in the annual report. Because of this, attempts to keep leases off the balance sheet will not affect stock price in an efficient capital market.

TAXES,THE IRS, AND LEASES

The lessee can deduct lease payments for income tax purposes if the lease is qualified by the Internal Revenue Service. Because tax shields are critical to the economic viability of any lease, all interested parties generally obtain an opinion from the IRS before agreeing to a major lease transaction. The opinion of the IRS will reflect the following guidelines:

1. The term of the lease must be less than 30 years. If the term is greater than 30 years, the transaction will be regarded as a conditional sale.

2. The lease should not have an option to acquire the asset at a price below its fair market value. This type of bargain option would give the lessee the asset’s residual scrap value, implying an equity interest.

3. The lease should not have a schedule of payments that is very high at the start of the lease term and thereafter very low. Early balloon payments would be evidence that the lease was being used to avoid taxes and not for a legitimate business purpose.

4. The lease payments must provide the lessor with a fair market rate of return. The profit potential of the lease to the lessor should be apart from the deal’s tax benefits.

5. The lease should not limit the lessee’s right to issue debt or pay dividends while the lease is operative.

6. Renewal options must be reasonable and reflect fair market value of the asset. This requirement can be met by granting the lessee the first option to meet a competing outside offer.

The reason the IRS is concerned about lease contracts is that many times they appear to be set up solely to avoid taxes. To see how this could happen, suppose that a firm plans to purchase a $1 million bus that has a five-year class life. Depreciation expense would be $200,000 per year, assuming straight-line depreciation. Now suppose that the firm can lease the bus for $500,000 per year for two years and buy the bus for $1 at the end of the two-year term. The present value of the tax benefits from acquiring the bus would clearly be less

than if the bus were leased. The speedup of lease payments would greatly benefit the firm and de facto give it a form of accelerated depreciation. If the tax rates of the lessor and lessee are different, leasing can be a form of tax avoidance.

THECASH FLOWS OF LEASING

In this section we identify the basic cash flows used in evaluating a lease. Consider the decision confronting the Xomox corporation, which manufactures pipe. Business has been expanding, and Xomox currently has a five-year backlog of pipe orders for the Trans-Honduran Pipeline.

The International Boring Machine Corporation (IBMC) makes a pipe-boring machine that can be purchased for $10,000. Xomox has determined that it needs a new machine, and the IBMC model will save Xomox $6,000 per year in reduced electricity bills for the next five years. These savings are known with certainty because Xomox has a long-term electricity purchase agreement with State Electric Utilities, Inc.

Xomox has a corporate tax rate of 34 percent. We assume that five-year straight-line depreciation is used for the pipe-boring machine, and the machine will be worthless after five years.

However, Friendly Leasing Corporation has offered to lease the same pipe-boring machine to Xomox for $2,500 per year for five years. With the lease, Xomox would remain responsible for maintenance, insurance, and operating expenses.

Simon Smart, a recently hired MBA, has been asked to calculate the incremental cash flows from leasing the IBMC machine in lieu of buying it. He has prepared Table 21.2, which shows the direct cash flow consequences of buying the pipe-boring machine and also signing the lease agreement with Friendly Leasing.

To simplify matters, Simon Smart has prepared Table 21.3, which subtracts the direct cash flows of buying the pipe-boring machine from those of leasing it. Noting that only the net advantage of leasing is relevant to Xomox, he concludes the following from his analysis:

1. Operating costs are not directly affected by leasing. Xomox will save $3,960 (after taxes) from use of the IBMC boring machine regardless of whether the machine is owned or leased. Thus, this cash flow stream does not appear in Table 21.3.

2. If the machine is leased, Xomox will save the $10,000 it would have used to purchase the machine. This saving shows up as an initial cash inflow of $10,000 in year 0.

3. If Xomox leases the pipe-boring machine, it will no longer own this machine and must give up the depreciation tax benefits. These tax benefits show up as an outflow.

4. If Xomox chooses to lease the machine, it must pay $2,500 per year for five years. The first payment is due at the end of the first year. (This is a break, because sometimes the first payment is due immediately.) The lease payments are tax-deductible and, as a consequence, generate tax benefits of $850 (0.34 ϫ $2,500).

Of course, the cash flows here are the opposite of those in the bottom line of Table 21.3.

Depending on our purpose, we may look at either the purchase relative to the lease or vice versa. Thus, the student should become comfortable with either viewpoint. Now that we have the cash flows, we can make our decision by discounting the flows properly. However, because the discount rate is tricky, we take a detour in the next section before moving back to the Xomox case. In this next section, we show that cash flows in the lease-versus-buy decision should be discounted at the after-tax interest rate (i.e., the after-tax cost of debt capital).